- Tags:: 📚Books

- Author:: Niall Ferguson

- Liked:: 4

- Link::

- Source date::

- Finished date::

- Cover::

Why did I want to read it?

What did I get out of it?

Introduction

The wife of an Oxford contemporary who entered politics once complained to him about his long working hours, lad of privacy, low salary and rare holidays - as well as the job insecuriyy inherent in democracy. ‘But the fact that I would put up with all that. he replied, ‘just proves what a wonderful thing power is.’ (p. xxii)

But is it? Is it better today to be in a network, which gives you influence, than in a hierarchy, which gives you power?

The worlds of hierarchies and networks meet and interact. Inside any large corporation there are networks quite distinct from the official ‘org. chart’. (p. xxiii)

When employees from different firms meet for alcoholic refreshments after work, they move from the vertical tower of the corporation to the horizontal square of the social network.

It also challenges the confident assumptions some commentators make today that there is something inherently benign in network disruption of hierarchical order. (p. 9)

Networks, networks everwhere

Unlike chimpanzees, we learn socially, by teaching and sharing. According to the evolutionary anthropologist Robin Dunbar, our larger brain, with its more developed neocortex, evolved to enable us to function in relatively large social groups of around 15o (compared with around fifty for chimpanzees).” Indeed, our species should really be known as Homo dictyous (network man’) because - to quote the sociologists Nicholas Christakis and James Fowler - our brains seem to have been built for social networks’! The term coined by the ethnographer Edwin Hutchins was distributed cognition. (p. 17)

Even today, the inhabitants of Indian villages are, at best, connected in a ‘social quilt… a union of small cliques where each clique is just large enough to sustain cooperation by all of its members and where the cliques are laced together’16 A key role in such isolated communities is played by the ‘diffusion-central’ individuals commonly known as gossips. (p. 18)

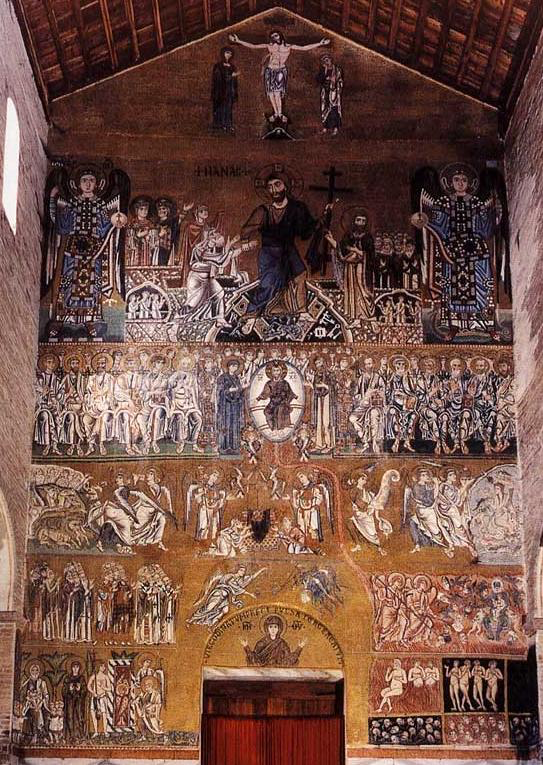

An old hierarchy, a Last Judgement scene in Cathedral of Santa Maria Assunta, Torcello (Venice).

Why hierarchies?

Historically, they begin with family-based clans and tribes, out of which (or against which) more complicated and stratified institutions evolved, with a formalized division and ranking of labour.’ (p. 21)

The crucial incentive that favoured hierarchical order was that it made the exercise of power more efficient: centralized control in the hands of the ‘big man’ eliminated or at least reduced time-consuming arguments about what to do, which might at any time escalate into internecine conflict.” (p. 22)

According to the philosopher Benoit Dubrewil, delegating judicial and penal power - the power to punish transgressors - to an individual or elite was the optimal solution for predominantly agrarian societies that required the majority of people simply to shut up and toil in the fields. (p. 22i)

Yet the defect of autocracy is obvious, too. No individual, no matter how talented, has the capacity to contend with all the challenges of imperial governance, and almost none is able to resist the corrupting temptations of absolute power. (p. 22)

In practice, of course, a large proportion of history’s autocratic rulers left a considerable amount of power to the market, although they might regulate, tax and occasionally interrupt its operations. That is why in the archetypal medieval or early-modern town - such as Siena in Tuscany - the tower representing secular power stands right next to, and indeed overshadows, the square where market transactions and other forms of public exchange took place (p. 23)

Informal networks, however, are different. In such networks, according to the organizational sociologist Walter Powell, ‘transactions occur neither through discrete exchanges nor by administrative fiat, but through networks of individuals engaged in reciprocal, preferential, mutually supportive actions … [that] involve neither the explicit criteria of the market, nor the familiar paternalism of the hierarchy (p. 23)

Stanford sociologist Mark Granovetter called, paradoxically, ‘the strength of weak ties?’ If all ties were like the strong, homophilic ones between us and our close friends, the world would necessarily be fragmented. But weaker ties - to the ‘acquaint-ances’ we do not so closely resemble - are the key to the ‘small world’ phenomenon. (p. 30)

Weak ties and viral ideas

strong ties matter more to the poor than weak ties, suggesting that the tightly knit networks of the proletarian world might tend to perpetuate poverty.* (p. 30)

Ronald Burt, american sociologist that studies social networks within organizations:

Brokers - people who are able to ‘bridge the holes’ - are (or should be) ‘rewarded for their integrative work because their position makes them more likely to have creative ideas (or less likely to suffer from group-think). In innovative institutions, such brokers are always appreciated. (p. 32)

As we shall see, an important but neglected measure of an individual’s historical importance is the extent to which that person was a network bridge. Sometimes, as in the case of the American Revolution, crucial roles turn out to have been played by people who were not leaders but connectors. (p. 46)

However, in most contests between an innovator-broker and a network inclined towards ‘closure’ (i.e. insularity and homogeneity) the latter often prevails.”

managers are more likely to be networkers than non-managers; that a ‘less hierarchical network may be better for producing solidarity and homogeneity in an organizational culture (p. 32).

The key point, as with disease epidemics, is that network structure can be as important as the idea itself in determining the speed and extent of diffusion.” (p. 34)

Varieties of network

Brokers in a network (e.g., managers) can easily be overloaded:

so many real-world networks follow Pareto-like distributions: that is, they have more nodes with a very large number of edges and more nodes with very few than would be the case in a random network. This is a version of what the sociologist Robert K called the Matthew effect, after the Gospel of St. Matthew: For unto every one that hath shall be given, and he shall have abundance: but from him that hath not shall be taken away even that which he bath ’. (…) There is, in short, ‘Preferential Attachment’. We owe this insight to the physicists Albert László Barabási and Réka Albert

When networks meet

Because of their relatively decentralized structure, because of the way they combine clusters and weak links, and because they can adapt and evolve, networks tend to be more creative than hierarchies. Historically, as we shall see, innovations have tended to come from networks more than from hierarchies. The problem is that networks are not easily directed towards a common objective . that requires concentration of resources in space and time within large organizations, like armies, bureaucracies, large factories, vertically organized corporations. Networks may be spontaneously creative but they are not strategic. (p. 43)

there seem to be consensus: few futurologists expect established hierarchies - in particular, traditional political elites, but also long-established corporations - to fare very well in the future.’ Francis Fukuyama is unusual in arguing that hierarchy must ultimately prevail, in the sense that networks alone cannot provide a stable institutional framework for economic development or political order. Indeed, he argues, hierarchical organization … may be the only way in which a low-trust society can be organized? By contrast, the iconoclastic British political operative Dominic Cummings hypothesizes that the state of the future will need to function more like the human immune system or an ant colony than a traditional state - in other words, more like a network, with emergent properties and the capacity for self-organization, without plans or central coordination, relying instead on probabilistic experimentation, reinforcing success and discarding failure, achieving resilience partly through redundancy. This may be to underestimate both the resilience of the old hierarchies and the vulnerabilities of the new networks - not to mention their capacity to fuse to form even newer power structures, (p. 45)

An example of the first is The Phoneix Project story:

we should probably expect continued network-driven disruption of hierarchies that cannot reform them-selves, but also the potential for some kind of restoration of hierarchical order when it becomes clear that the networks alone cannot avert a descent into anarchy. (p. 48)